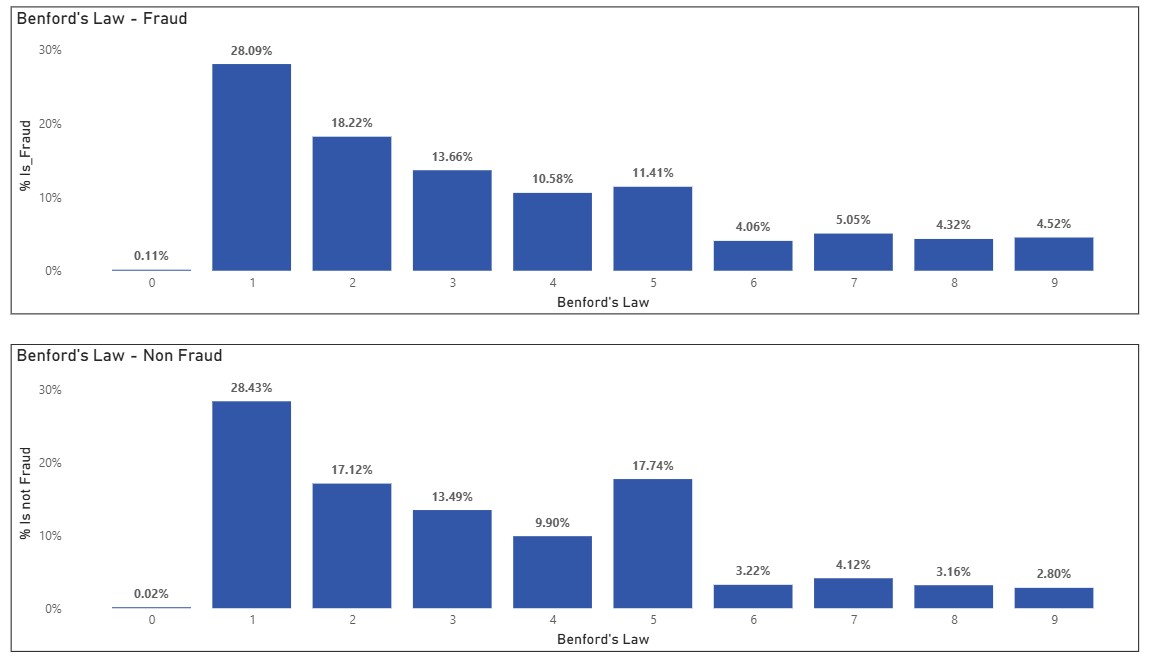

Exploratory data analysis on Fraud Transactions

Introduction

This dataset, sourced from a Kaggle competition, focuses on transaction-level fraud detection.

It can be found on the following link: https://www.kaggle.com/competitions/ieee-fraud-detection/data

Each row represents a single transaction and is labeled as either fraudulent or non-fraudulent. Therefore, the objective is to build a model that can classify the transactional integrity, rather than identifying fraud related to specific cards or individuals.

The dataset includes over 300 anonymized variables (features), most of which are numerical, which is advantageous for training many Machine Learning models. Detailed information regarding the meaning of each feature is limited: only a high-level description for various column groupings is provided, which will be detailed later.

Visual Exploration and Statistical Analysis

Data exploration with visuals is a good starting point to get to know the data in a more informal way.

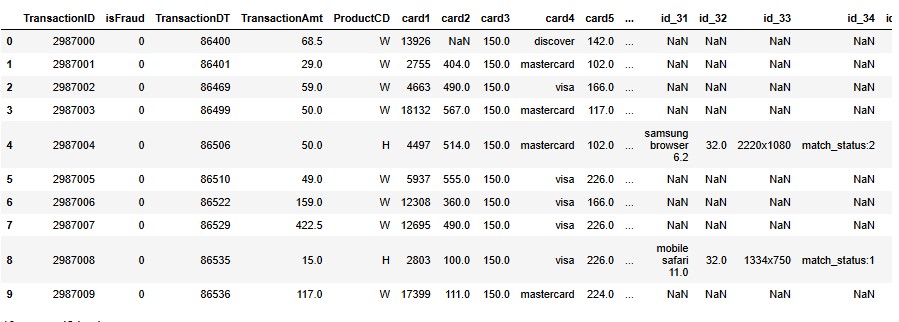

Products

A separate pie chart analysis for the fraudsters and non fraudsters indicates that for product C relatively more fraud occurs, which can be a very useful starting insight.

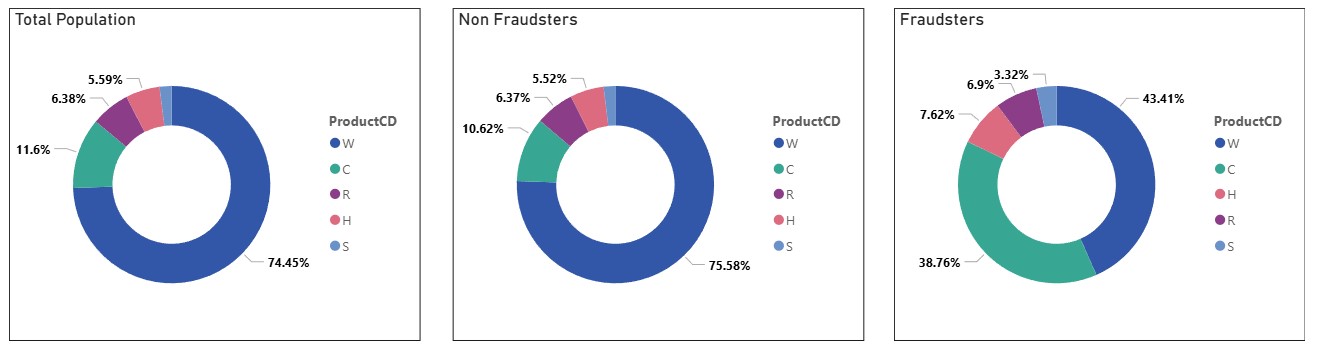

Email Domains

Some domains show a larger blue proportion, meaning disproportionately high fraud rates:

■ protonmail.com

■ outlook.es

■ mail.com

■ aim.com

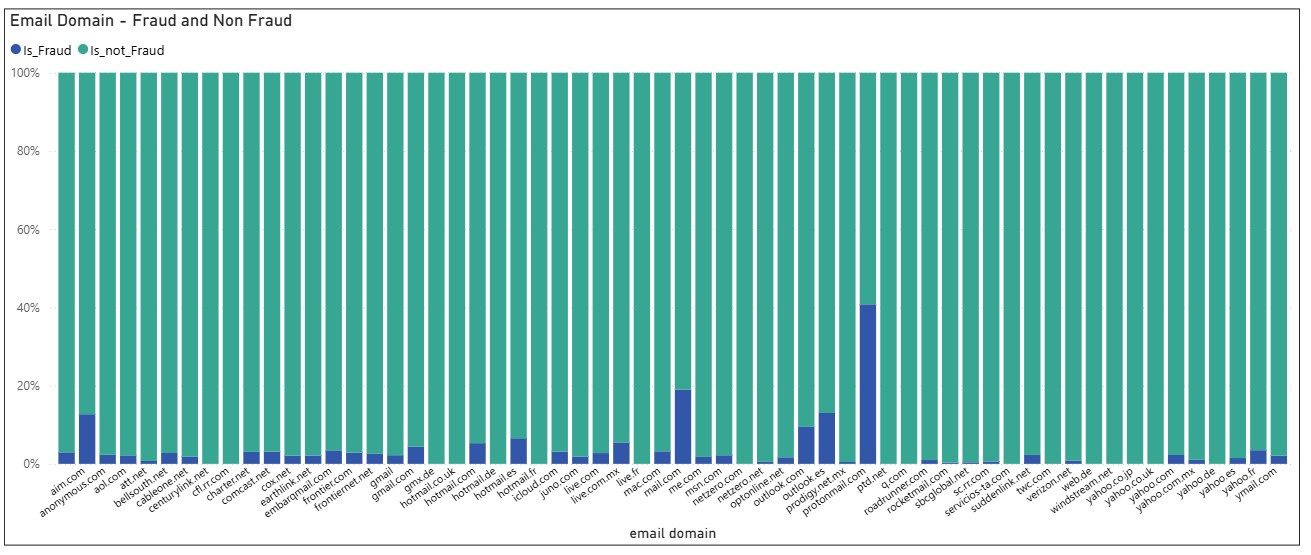

Benfords Law

Another tool or technique that can be very useful to spot fraud cases is related to Benford's Law.

Benford's Law looks at the frequency of the first digit in a dataset. In many real life datasets, the first digit of numbers is not uniformly distributed: 1 appears as the first digit most of the time, followed by 2, 3 and so on.

In legitimate datasets numbers tend to follow this law in a natural way, but when humans fabricate numbers they usually tend to do so by following unrealistic patterns. For instance, avoiding extremes like 1 and 9, and overuse on central numbers such as 5 or 6.

In this dataset both fraud and non fraud roughly follow Benford' s law. Why roughly? Because we are not supposed to see a spike around number 5, for both cases. 5 is a round number where fraudsters might choose mid-range numbers.

A possible reason for why we might see Benford's law on both cases might be due to exchange rates. In this dataset all transaction amounts were converted to dollars, which created the condition of the law naturally emerged.

Descriptive Statistics

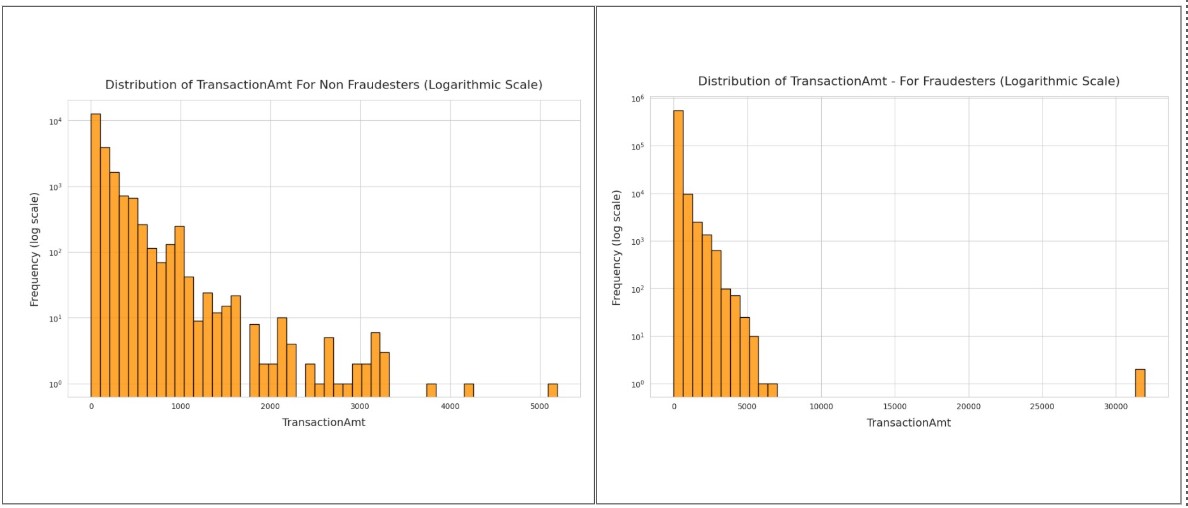

Histogram

Both Fraud and Non-Fraud translation amounts follow a right skewed distribution, where the majority of transactions occur at low values (around 200) and a long tail extending to higher amounts.

The fraud histogram’s bar at low transaction amounts are much taller than those of non-fraud when normalized. This might suggest that fraudsters do “test” cards with small charges.

Main Stats Table

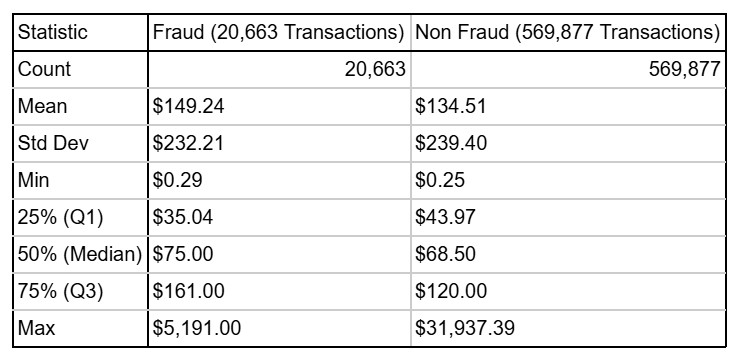

Lets now observe the mains statistics regarding transaction amount between Fraudsters and Non Fraudsters.

In terms of Volume, Non Fraud transactions are vastly larger, containing over 27 times the number of transactions.

Both sets are heavily right-skewed (mean is much higher than median), but the typical transaction (median) in Fraud is slightly higher than in Non-Fraud.

Maximum Outliers: Non-Fraud has a far more extreme outlier, with a maximum transaction amount of almost $32,000.

Distribution: The transaction amounts in Fraud are more spread out in the top half: its 75th percentile ($161.00) is higher than Non Fraud ($120.00), indicating that while Non Fraud has the extreme maximum, a larger proportion of transactions in Fraud fall into the moderately higher range.

The statistics are quite similar between Fraudesters and Non Fraudsters. Fraudsters typically want to go unnoticed and behave similarly to the rest of the population. This makes the fraud tend to go undetected. Fraudsters plan every step very carefully, down to the maximum detail, which makes their detection difficult. Which makes the transaction amount feauture a weak predictor for fraud. As you can see in these stats, Fraudsters tend to keep a similar amount as in real life.Regular small payments is a really good technique to avoid getting noticed, and they know. Another red falg could be checking for these transactions over time: Usually a fraudster makes smaller payments before starting to make large payments. This is to check if the card is still active before placing a bet. However in this dataset this is not possbile to check as we do not have card transaction activity, but rather fraudulent transactions.

Maybe better predictors than transaction amount could be "velocity" (number of transactions per minute / day) and device / location mismatch.

Time of the Day

Another interesting feature this dataset has it's TransactionDT. Even though they are not giving us the description of this feature, someone on the Discussion forum wrote the following: timedelta from a given reference datetime (not an actual timestamp) “TransactionDT first value is 86400, which corresponds to the number of seconds in a day (60 * 60 * 24 = 86400) so I think the unit is seconds. Using this, we know the data spans 6 months, as the maximum value is 15811131, which would correspond to day 183.

Variable Selection - Correlation for numerical Variables

This dataset has over 300 variables, but only a few can actually predict the target variable. How to find these variables? We can start by measuring the correlation between the target and these numeric variables. It will give us a quick screening for which variables we should keep for further analysis.

What Social Network tells us about Fraud

Most people have have social media and they share a lot of their personal information. Their friends, family, relationships, it is all in the internet. This allows analysts to do a perfect mapping for someone.

If traditional techniques fail to spot fraud, social network can have a helpful role by giving more insights and more clues by taking a look at people and their connections. This is called guilt by association. If we know that person A has five friends that are fraudsters, how likely it is that person A is a fraudster?